[Ed. note: This post is part 1 of a multipart look at corruption, deceit, greed, and abuse of power in Fort Smith, Arkansas, primarily (though not entirely) through the lens of the police department.]

Capt. Jarrard Copeland of the Fort Smith Police Department Office of Professional Standards sat smugly on the witness stand. This was a hearing on a motion for a preliminary injunction, which the plaintiffs–three of Copeland’s fellow officers of the FSPD–had filed a week earlier.

The plaintiffs’ lawsuit, alleging violations of the Arkansas Whistle Blower Act, named Capt. Copeland and several other FSPD officers as defendants. At issue in this hearing was whether Capt. Copeland or any other named defendants should be permitted to question the plaintiffs about conversations the plaintiffs had had with their lawyer and whether any of the plaintiffs had revealed confidential FSPD information. This investigation was in response to a blog post detailing how a street-crimes detective had gotten naked and had a prostitute masturbate him before arresting her for prostitution.

According to Copeland, he had received complaints from two undercover officers–an assertion that we’ll come back to a couple of times–who were “concerned about their identities being released to someone outside the agency.” Copeland testified that he had already interviewed the corporal who had taken a picture of the probable-cause affidavit at the Sebastian County Jail, and that he had interviewed one of the plaintiffs–Sgt. Rick Entmeier–to ask questions about what Entmeier knew about that affidavit and what Entmeier had discussed with his attorney.[footnote]Full disclosure: I am the lawyer for all three plaintiffs in this story.[/footnote] Next, Copeland wanted to interview Sgt. Don Paul Bales.

The Plaintiffs’ lawyer began his cross examination of Capt. Copeland and quickly moved to the substance of the investigation and the procedures being followed (emphases added).

Q. Is Sergeant Entmeier actually named in the [undercover officers’] complaints?

A. Yes.

Q. And you said this was a class A complaint?

A. Yes.

Q. So then did you actually provide [Sgt. Entmeier] with written notice detailing the allegations as well as his rights and responsibilities relative to the investigation?

A. No.

Q. Isn’t that how it’s supposed to work when you investigate a class A complaint?

A. If he’s listed as a suspect.

Q. And you said he’s —

A. He’s listed in the complaint but he’s not listed as a suspect. He’s just listed as a possible person who may have gotten the information. No one said that they believed Sergeant Entmeier gave you this information. They just said that you represent those three so common sense would tell a normal person that it might have been one of those three that gave it to you. We didn’t feel like that rose to the level of naming them a suspect.

Q. So who was named as a suspect in the complaint?

A. Nobody.

Q. So my clients were the only people named in the complaint?

A. Yes. And Carson Addis. I believe Carson was only named in the one complaint.

Q. Did Carson Addis say that he had shown the photo to Don Paul Bales?

A. No.

Q. Did he say that he had shown it to [Plaintiff] Wendall Sampson?

A. I don’t think so. He said that he had talked to Wendall about it.

Q. So you have got four or five people, one of whom is Sergeant Entmeier. You interviewed him. Don Paul Bales wasn’t mentioned by Sergeant Addis, yet Don Paul Bales is the next person you want to talk to?

A. Yes.

Q. But he’s not a suspect. You just want to talk to him despite nobody having said that he actually did anything?

A. No one said anybody did anything.

After Plaintiffs’ attorney was finished questioning Captain Copeland, Judge James O. Cox asked the witness:

So to clarify one thing. You said, well, “nobody said anybody did anything.” You just got a complaint or two complaints where something was done these officers were concerned about. They didn’t say who did it.

COPELAND: Right.

Based on Copeland’s testimony, which Judge Cox described as “very candid,” the Court denied Plaintiffs’ request for an injunction and allowed Copeland’s interviews of the Plaintiffs to proceed.

One wonders whether Judge Cox would have found Copeland’s testimony nearly as credible, or if Copeland would have been allowed to continue his feverish efforts to have Sgt. Bales terminated, if the judge had known that Capt. Jarrard Copeland was lying to his face, in open court.

“No one said anybody did anything.”

On August 6, 2014, Detective Scott Campbell sent an Inter-Office Memo to Capt. Copeland with the subject line “Attempted Violation of A.C.A. 25-19-105(b)(10)(A).” In it, he notes that the Plaintiffs’ attorney had submitted an AFOIA request for “any and all arrest reports…involving Detective Scott Campbell in the arrest of a suspected prostitute” to the FSPD. His memo claimed that he was and undercover officer[footnote]Hold that thought. We’ll come back to it again.[/footnote] and the fact that someone outside the FSPD knew that Campbell had made a prostitution arrest was a violation of the provision of the AFOIA that covers undercover police officers’ identities. Campbell’s complaint stated:

It is my belief that [the Plaintiffs’ attorney] received the information regarding this prostitution arrest from one or more of the clients that he is representing in a lawsuit against the Police Department, namely Sergeant Don Paul Bales, Sergeant Rick Entmeier, and Corporal Wendall Sampson.

Campbell’s complaint further asserted violations of three FSPD rules by one or more of the Plaintiffs based on Campbell’s belief that the Plaintiffs had released his identity.

The next day, August 7, Cpl. Johnny Bolinger–the street-crimes detective referenced in this post–filed an Internal Complaint with FSPD Chief Kevin Lindsey. In it, he asserted that he is an undercover detective, that the release of his identity was a violation of FSPD policy, and that

It is my belief that [the Plaintiffs’ attorney] received the information regarding this prostitution arrest from one or more of the clients he is representing in a lawsuit against the Police Department, namely Sergeant Don Paul Bales, Sergeant Rick Entmeier, and Corporal Sampson, or Carson Addis since that is where I believe the original photograph of my PC affidavit originated.

Bolinger’s complaint also asserted specific FSPD-rules violations attributable to one or more Plaintiffs.

Now, just at face value, it seems patently absurd for Capt. Copeland to say on August 29, 2014, that “no one said anybody did anything” in the August 6 and August 7 complaints. Campbell and Bolinger both explicitly stated that they believed (i.e., they suspected) the Plaintiffs of having released their identities. Of course the Plaintiffs were named as suspects.

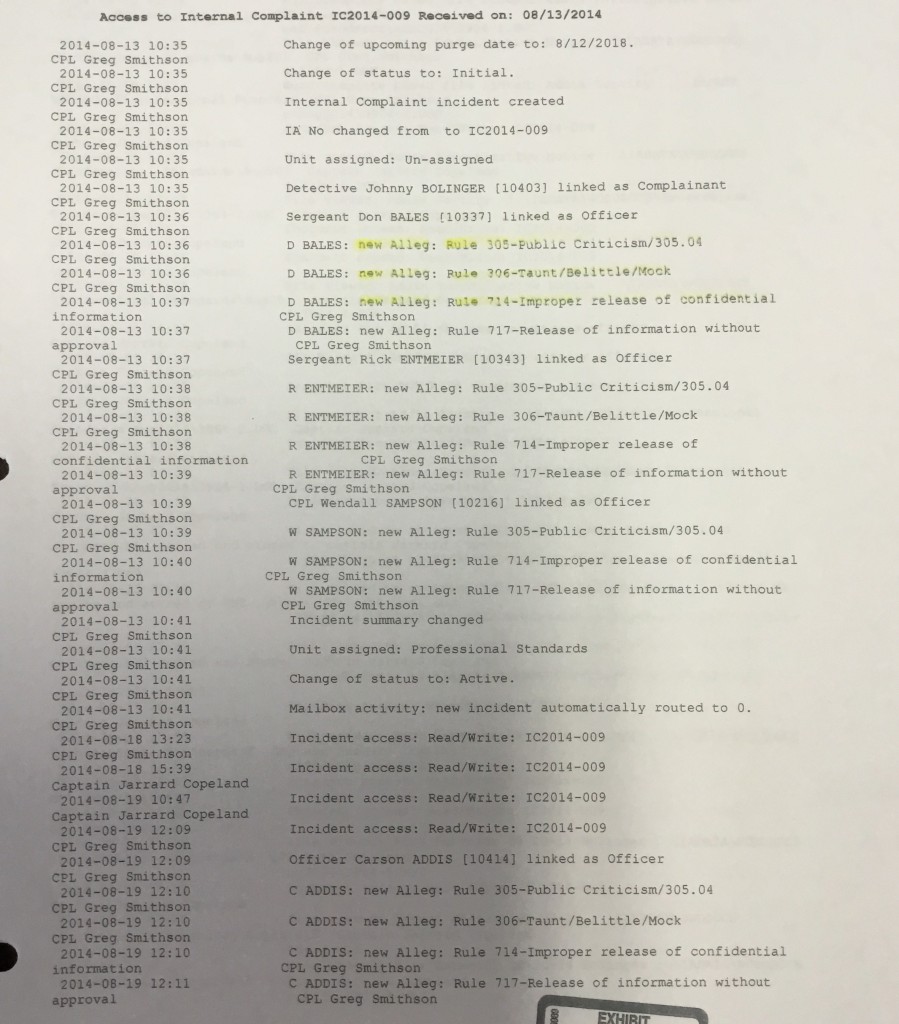

The thing is, Copeland knew this was a lie at the time he was saying it. In the IA Pro system–an FSPD computer program that tracks internal investigations–Cpl. Greg Smithson, who works as Copeland’s second-in-command in the Office of Professional Standards, created a new file on August 13, 2014, in response to Det. Bolinger’s complaint. From the first page of the IA Pro audit trail, you can see (click to enlarge)…

that Smithson first listed Johnny Bolinger as “Complainant.” He then proceeded to add Sgt. Bales as “Officer,” which is the IA Pro label for the officer suspected of violating a departmental policy or rule. Smithson then listed three allegations against Bales, as laid out in Bolinger’s complaint.

Smithson repeated this procedure with Sgt. Entmeier and Cpl. Sampson as well, listing each as “Officer” (e.g., suspect) and inputting the allegations against each as made by Bolinger.

Also notable on this first page is the fact that Carson Addis was not put into the system as a suspect until August 19. That is, the officer who actually took the photo of the PC affidavit at the Sebastian County jail was not included as a suspect, despite being named in Bolinger’s complaint, until six days after the Plaintiffs had been named as suspects. That becomes more noteworthy when you turn to page 2 of the audit trail.

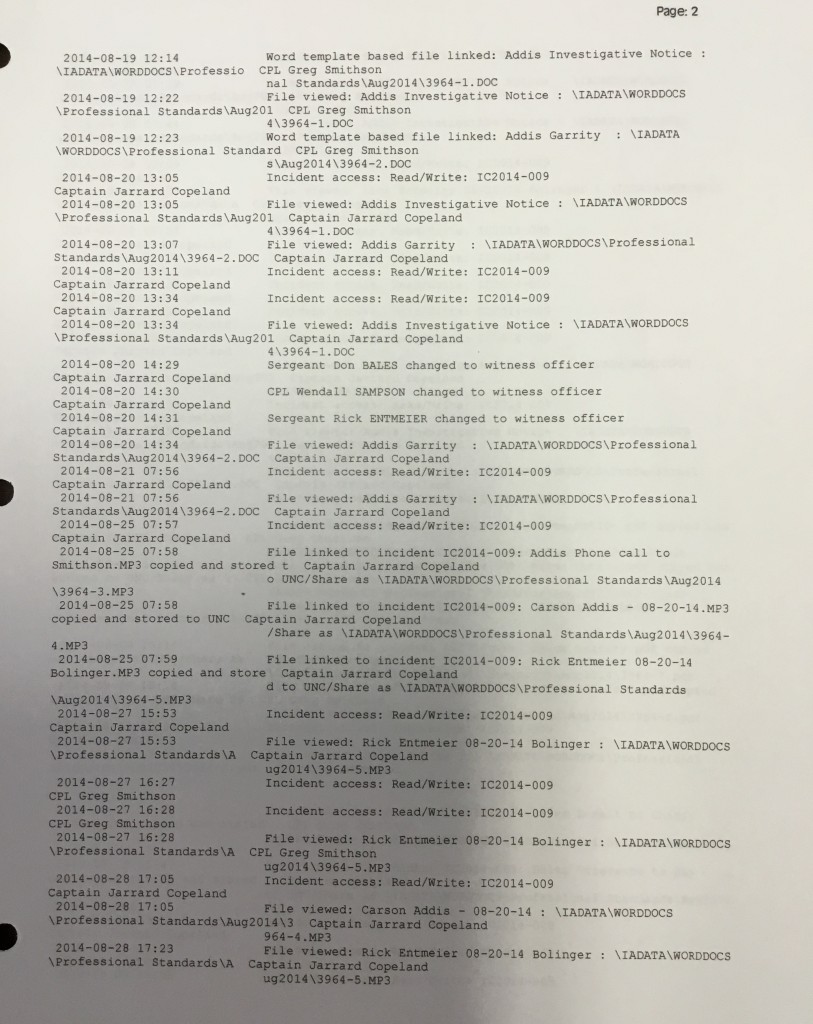

As you can see, once Addis was entered into IA Pro as a suspect, Capt. Copeland and Det. Smithson then created a Notice of Investigation for Addis and a “Garrity Warning,” both of which are given to an officer before he is interviewed as a suspect in an internal investigation. Addis had literally been a suspect in the IA Pro system for five minutes when Smithson began drafting the Investigative Notice.

The following day, August 20, demonstrates Copeland’s actual knowledge that his later testimony was a lie:

- Between 1:07 and 1:34, Copeland opens the files for Addis’s investigative notice and Garrity Warning, presumably to edit and print those documents.

- At 1:37 pm, Copeland and Smithson provide Carson Addis with the required notice and warnings and interview Addis regarding the allegations in Bolinger’s complaint.

- At approximately 1:39 pm, Addis says that he took the picture of the affidavit because jail staff were wondering whether the techniques described in it were legal, and Addis wanted to ask one of his supervisors.

- At about 1:40 pm, Addis specifically states that he emailed the photo to Sgt. Rick Entmeier, among other people. Copeland asks Addis, around 1:42 pm, whether Sgt. Entmeier told Addis why he wanted the photo, what he was going to do with it, and/or whether Entmeier thought the behaviors in the affidavit were illegal. Addis replies that Entmeier did not say anything about any of those questions.

- Smithson then asks, “Do you think it was odd [Entmeier] asked you to send it to his personal email, rather than his PD email?”

- Following some lengthy back-and-forth over whether Addis was trying to get Bolinger “in trouble” by taking that picture, Addis’s interview ends at 1:54 pm.

- At 2:29 pm, Jarrard Copeland goes back into the IA Pro system and changes all three of the Plaintiffs’ statuses to “witness officer.”

- At 3:16 pm, Copeland and Smithson interview Sgt. Rick Entmeier. No notice or warnings are given. During the interview, and despite the language of the complaints and the fact that Entmeier had been a suspect in the IA Pro system, Copeland specifically tells Entmeier, “we haven’t given you a notice of investigation because you’re not accused of doing anything.”

This much is indisputable: (1) Rick Entmeier was entered into IA Pro on August 13 as a suspect; (2) Carson Addis was entered into IA Pro on August 19 as a suspect based on the same complaint that had referenced Sgt. Entmeier; (3) nothing that Addis said in his August 20 interview obviated whatever suspicions about Entmeier or the other Plaintiffs had justified making them suspects in the first place.

Yet, as soon as Copeland decided he was going to start interviewing the Plaintiffs, he changed the Plaintiffs to witnesses. Why? Because a suspect officer is entitled to notice/warnings and the presence of counsel in this kind of interview. Copeland and Smithson wanted to know how Plaintiffs’ attorney got Bolinger’s name, so they certainly did not want the Plaintiffs bringing their attorney to the interviews.

Thing is, Copeland’s desire to avoid Plaintiffs’ bringing their attorney to the interviews does not change the reality that Plaintiffs were suspects right up until it was not convenient for them to be suspects.

More importantly, it does not make Copeland any less of a liar when he sat on the witness stand, under oath, and told the Court “no one said anybody did anything” or that there were no suspects in the investigation.

Under Arkansas law, perjury is defined as where a person, “in an official proceeding[,] knowingly [m]akes a false material statement under an oath required or authorized by law.” A motion hearing in circuit court is an official proceeding. Copeland was under oath. His statement was material, inasmuch as it was specifically what Judge Cox asked him to verify before finding that the interviews were on the up-and-up. Most importantly, his material statement was knowingly false, as demonstrated above.

Surveillance

As mentioned, Cpl. Smithson opened the IA Pro file on August 13 based on Bolinger’s August 7 complaint.

The day before, on August 12, Capt. Copeland had received a “tip” from another officer that Sgt. Bales and his attorney were going to lunch in Bales’ city-owned police vehicle. Copeland, who has been with the department for years, should have been well aware that officers throughout the department use their city-owned vehicles for errands, including taking kids to and from school, going to the grocery store, etc. Nevertheless, when he heard that Bales and Bales’ attorney were going to lunch, he literally had two other FSPD officers drive to where Bales was eating, stake out Bales’ car, and take pictures of Bales and his attorney leaving the restaurant.

The officers then followed Bales and his attorney back to the attorney’s office, taking more photos along the way. In all 31 photos were taken, and these were given to Copeland and Smithson, who then opened a file in IA Pro, naming Bales as a suspect and accusing him of violating department policy.

Bales was never informed of this investigation, nor was he told that it had been treated as a class B violation. Bales was never given a chance to respond to the allegation, was never provided with any kind of due process, and was not even questioned about the allegation. Worse still, he was never told that the department considered the violation to have been sustained, or that he was deemed to have received oral counseling as discipline for this violation.

Similarly, during the August 29 hearing, Copeland did not mention that he had been monitoring the Plaintiffs’ facebook pages since just after their whistle-blower suit was filed in January 2014, taking screenshots of any posts that referenced their lawsuit, Daily & Woods, or anything that Copeland deemed “offensive.” Nor did he mention that he and Smithson and Chief Lindsey had met with attorneys from Daily & Woods in July 2014 to discuss the Facebook posts and whether the PD was allowed to discipline the Plaintiffs for those posts. This would become relevant shortly after the August 29 hearing, when Chief Lindsey opened an additional investigation into the Plaintiffs based on Copeland screenshots of their Facebook pages.

Confidential & Undercover

The premise of the internal complaints filed by Bolinger and Campbell was that they were undercover officers and, thus, the release of their identities to someone outside the FSPD was a breach of rules and policies. At first blush, this seems to make a little sense. But it rapidly falls apart when you learn that the FSPD, using public funds, already guaranteed that the information would be disseminated outside the department.

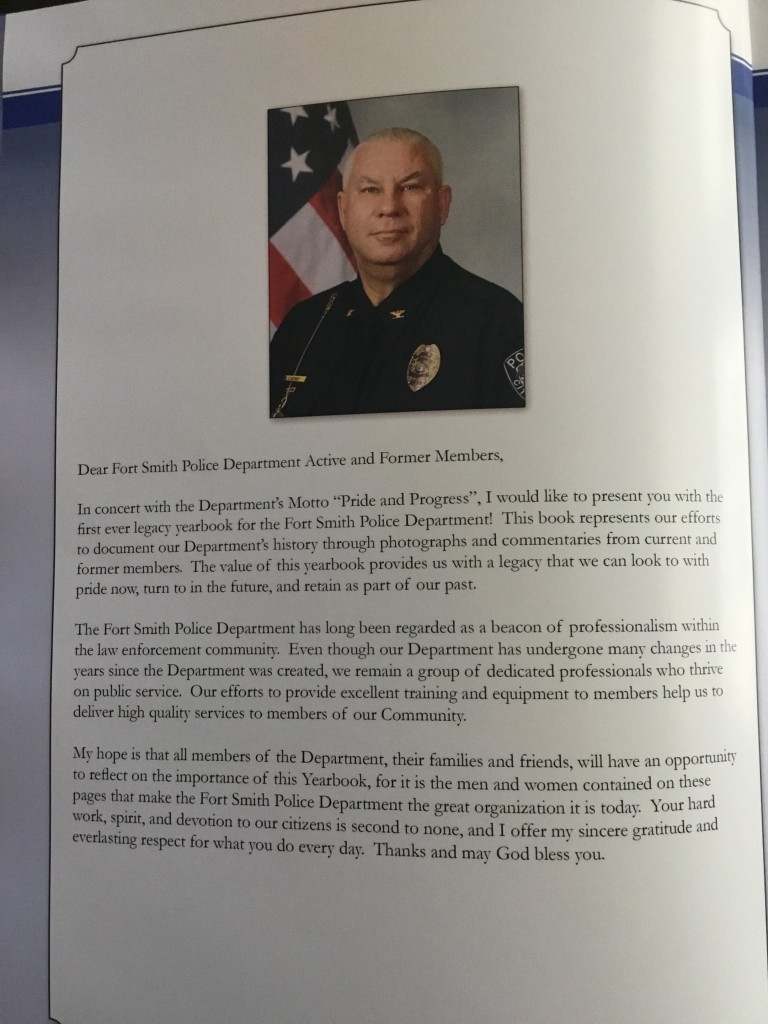

This is because the FSPD contracted to have a legacy album (read: yearbook) created. Participation was mandatory, photographs were done while on-duty, and every detective was included by face, name, and department in which he or she works. And, if you turn to the first page of that yearbook, you see the Chief’s statement:

Right there, last paragraph, it says, “My hope is that all members of the Department, their families and friends, will have an opportunity to reflect on the importance of this Yearbook.” His questionable grammar aside, that statement is pretty straightforward, and it says nothing about protecting allegedly “confidential” information that may be contained in the Yearbook.

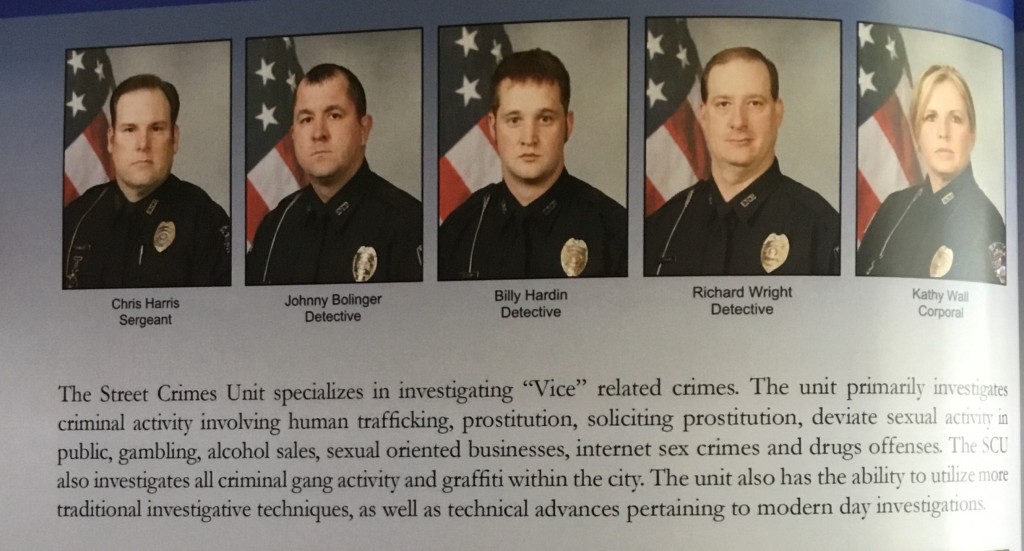

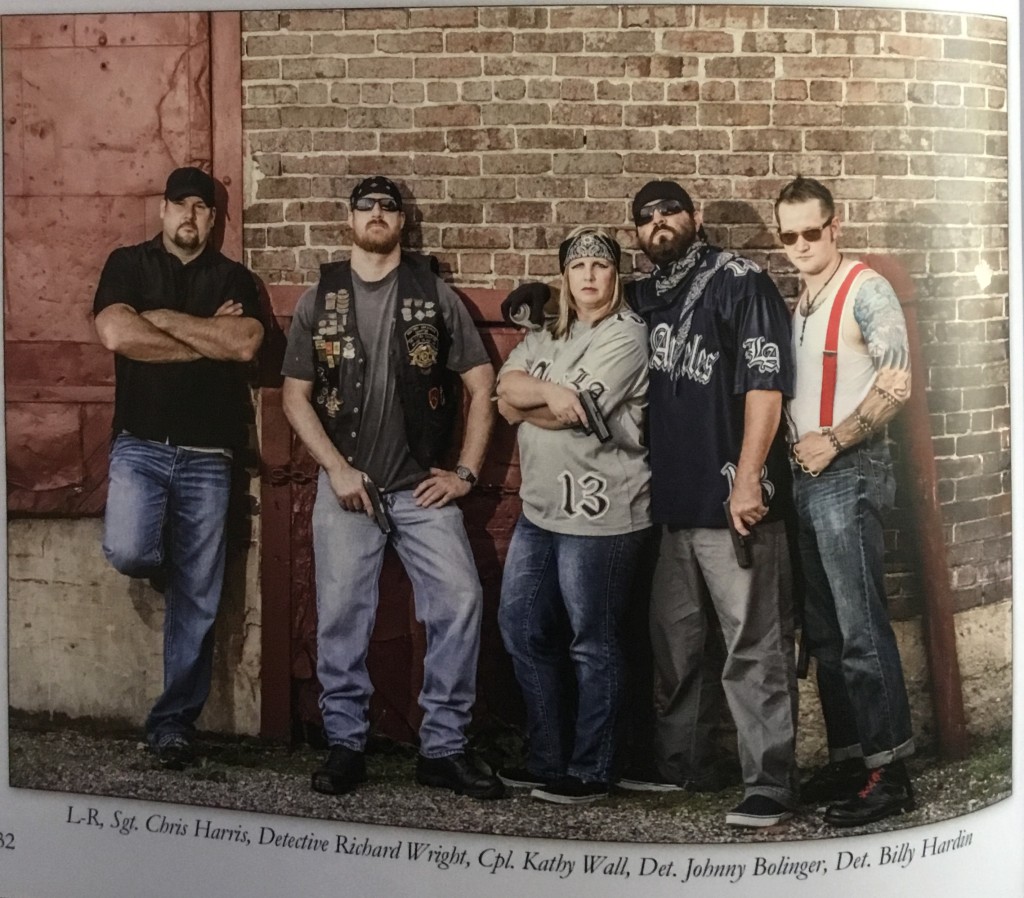

If you flip through the Yearbook, you will come across pages for each division and branch within the FSPD, including, for example, Street Crimes, where you would see this:

That appears to be a picture of, among others, Detective Johnny Bolinger, identified by name and face. Just below the photos, it says that the Street Crimes Unit investigates prostitution, and that they have “the ability to utilize more traditional investigative techniques, as well as technical advances pertaining to modern day investigations.”

“But wait,” you may be thinking. “Obviously an undercover officer does not go out in his uniform, so it’s not like this picture would necessarily identify Bolinger to an outsider.” To that, I would first say that any picture of Bolinger is more identifying than just his name would be, which is what Copeland was using as the basis for his investigation of the Plaintiffs. I would then say, assuming you are correct, the FSPD has taken care of that by providing a picture of the detectives in street clothes as well, again with corresponding names:

Similarly, the Narcotics Unit has its own page in the yearbook, on which you could find Detective Scott Campbell:

Again, this is a yearbook that any person can walk in off the street and buy. (I know this because that is exactly how I got this book.) Indeed, it would arguably subject to release under the AFOIA, though I imagine the FSPD would put up some resistance to that release. But Copeland and the rest maintained, start to finish, that the names of two detectives were so confidential, so top secret, that any alleged utterance of those names to someone outside the department was a huge breach of rule and policy.

Speaking of Campbell

You might have noticed that the IA Pro file, as well as the interviews of Addis and Entmeier referred only to the complaint filed by Johnny Bolinger and said nothing about the Scott Campbell complaint. You might have even wondered why that was.

The short answer is another lie in Copeland’s testimony.

To be protected from release under the AFOIA, a police officer must be (a) working in an undercover capacity and (b) have registered himself as an undercover officer with Arkansas State Police Office of Minimum Standards.

At the time of the AFOIA request that referenced Scott Campbell, however, Campbell was not registered with Minimum Standards. On August 1, 2014, following the AFOIA request, someone at the FSPD caught Campbell’s lack of registration, and a letter was quickly sent to Minimum Standards that included Campbell’s name. Campbell then filed his internal complaint on August 6, after his registration was confirmed.

Except that registration was not retroactive. If he was not properly registered with Minimum Standards as of the date of the AFOIA request, the release of his name was not a violation of the AFOIA. And, since the FSPD policy regarding release of confidential information makes an exception for information that is subject to AFOIA, the release of Campbell’s name could not have been a violation of that policy.

Copeland and Smithson apparently realized this fact, which would explain why no IA Pro file was opened with respect to Campbell’s complaint. Yet, on August 29, it appears that Copeland did not bother to inform the attorney for the FSPD about Campbell, as attorney Colby Roe told the Court:

Those two complaints were from two police officers who are undercover police officers within the department. They are on the registry in Little Rock as undercover officers, and those officers’ concerns, their basis for their complaints were that their identities as undercover officers had been disclosed to someone outside of the department.

When it was Copeland’s turn to answer questions, he ran with the lie:

Q. The two complaints that you just identified, what were the bases or the concerns of these officers in their complaints?

A. Both officers are undercover officers and they were concerned about their identities being released to someone outside the agency.

“Professional” Standards

Copeland’s lies–and the way in which they amount to perjury–are straightfoward enough. So why is the additional information included in this post? After all, none of these additional facts, on its own, is directly related to the August 29 hearing.

However, Copeland’s “very candid” testimony hinged on getting Judge Cox to believe that (a) the Plaintiffs were not suspects in that investigation, (b) the FSPD had a vested interest in protecting Bolinger and Campbell’s names from release to anyone outside the department; (c) Copeland was not using the investigation as retaliation for the whistle-blower lawsuit, and (d) that Copeland would not do anything to interfere with Plaintiffs’ relationship with their attorney.

Had this additional information been known on August 29, along with the fact that Copeland was lying about the Plaintiffs’ not being suspects, it seems highly unlikely that Copeland could have satisfied any of those prongs to the satisfaction of the Court, let alone all of those prongs. In turn, Copeland would not have been allowed to continue his witch-hunt investigation.

On a broader level, though, what does all of this say about the fairness and impartiality of internal investigations done under Jarrard Copeland’s watch at the FSPD? What does it say about Copeland that he, a captain in a position of relative power over basically the entire FSPD, would perjure himself so blatantly in court just to keep an investigation going into three other officers?

The hypocrisy here is overwhelming. Copeland chastised Carson Addis for doing something that might “get Johnny in trouble” when all Addis was doing was finding out if Bolinger’s actions were legal. Meanwhile, Copeland is actively, nefariously plotting to get one or more of the Plaintiffs in trouble based on some absurd, trumped-up allegations, and he was willing to risk felony perjury charges to do so.

I wish I could say that Copeland’s actions were unique within the FSPD. That, however, would be a lie, and–unlike Jarrard Copeland–I prefer to rely on the truth to make my point.

1 comment for “Anatomy of Corruption, Pt. 1: The Lies They Tell”